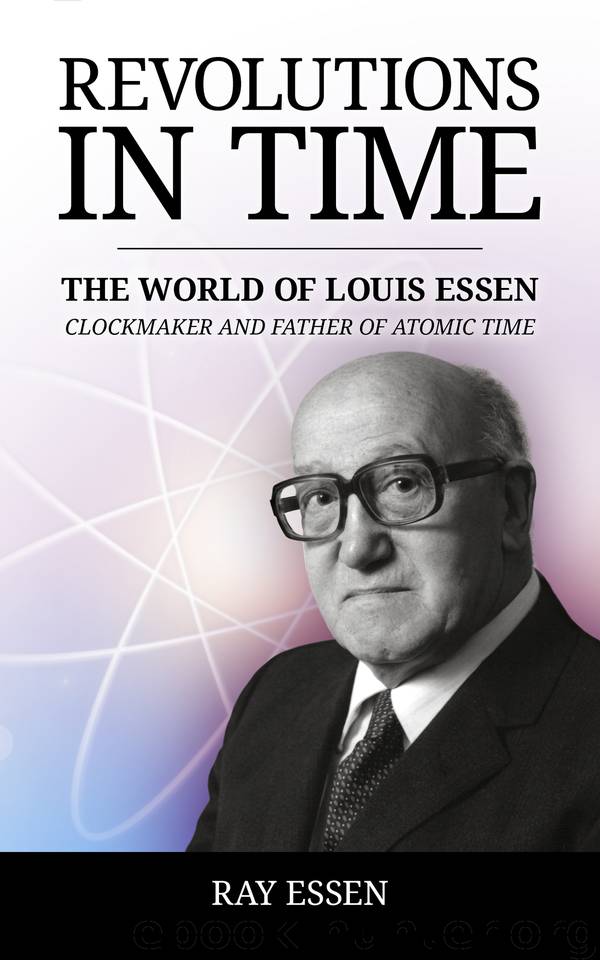

Revolutions in Time: The world of Louis Essen, clockmaker and father of atomic time by Essen Ray

Author:Essen, Ray [Essen, Ray]

Language: eng

Format: epub

Published: 2020-07-07T16:00:00+00:00

13. The Flying Bedstead

“I invited the director to come and witness the birth of atomic time.”

Louis Essen (1908-1997). Physicist

T he new director was in no position to give Essen the green light to build an atomic clock in 1950 despite his initial enthusiasm. The prevailing attitude in Britain was that the United States would soon have several working atomic clocks, making Essen’s contribution largely irrelevant. Also, Britain’s electronics industry had come to believe that the atomic clock was not a commercially viable product. Some pundits thought that it would take many years of effort to develop a clock with the required accuracy. This came at a time when NPL’s priority was to help British industry become more competitive in overseas markets and the director could not afford to indulge in arcane projects with little chance of success.

Bullard had been forewarned that resources may have to be redeployed in the event of an emergency. The anticipated crisis arose largely because of Britain’s military involvement in the Far East. There was a long-running guerrilla war, known as the Malayan Emergency, and the Korean War had just started in 1950. Although NPL was a civilian establishment, the military occasionally requested help with some of the less secret aspects of a problem, particularly those requiring knowledge of precise measurement techniques.

Around this time, Essen was asked to determine how the speed of radio waves varied depending on atmospheric conditions. It was especially important to understand how the presence of water vapour in the atmosphere could affect distance-measurement equipment used for surveying and airborne radar systems used by the Royal Air Force. Essen simulated the atmospheric conditions in the laboratory and took hundreds of measurements in an experiment that would continue on and off for the next five years.

***

Stepping through the double-width doors of Building 5 at the National Physical Laboratory was like stepping back in time. The yellow-brick and slate-roofed building had been erected in 1906 and its large, open layout was ideal for housing the heavy machinery needed to study problems associated with electric power distribution and the industrial application of electricity. Later, in the 1930s, the Radio Department under the leadership of Robert Watson Watt had occupied part of Building 5.

By the 1950s, the crackle of electric sparks and the smell of engine oil had disappeared and the sign above the entrance changed from ‘Electrotechnics’ to ‘Electricity 1 and Electrotechnics’. A mezzanine floor was added to the original hall and a row of small offices were constructed with windows facing Bushy House. Louis Essen had moved out of Bushy House once the war was over and shared the end office in Building 5 with two colleagues from the Electricity Division. Only the quartz clocks, along with their associated electronics, remained in the basement of Bushy House.

Every day except Sunday, Essen’s bicycle could be seen leaning against the outside wall of Building 5. He could not afford a car and there was no television at home. His wife Joan, like everyone else in Britain, had learnt to cope with food rationing which was still in force long after the war had ended.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

Hit Refresh by Satya Nadella(9141)

When Breath Becomes Air by Paul Kalanithi(8449)

The Girl Without a Voice by Casey Watson(7890)

A Court of Wings and Ruin by Sarah J. Maas(7856)

Do No Harm Stories of Life, Death and Brain Surgery by Henry Marsh(6944)

Shoe Dog by Phil Knight(5271)

The Rules Do Not Apply by Ariel Levy(4974)

A Higher Loyalty: Truth, Lies, and Leadership by James Comey(4966)

Hunger by Roxane Gay(4929)

Tuesdays with Morrie by Mitch Albom(4790)

Everything Happens for a Reason by Kate Bowler(4746)

The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks by Rebecca Skloot(4592)

Millionaire: The Philanderer, Gambler, and Duelist Who Invented Modern Finance by Janet Gleeson(4482)

How to Change Your Mind by Michael Pollan(4358)

All Creatures Great and Small by James Herriot(4326)

The Money Culture by Michael Lewis(4211)

Man and His Symbols by Carl Gustav Jung(4139)

Elon Musk by Ashlee Vance(4129)

Tokyo Vice: An American Reporter on the Police Beat in Japan by Jake Adelstein(3997)